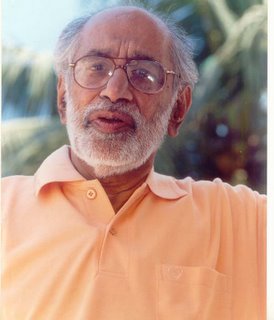

MY grandfather Sundara Ramaswamy, who died over a month ago, leaves behind a rich legacy shaped by his written works — novels, poems, short stories, critical essays. But for me, he was just Grandpa.

My earliest memories of him are of a bald man sitting in his room, a wall entirely made of glass, loudly dictating Tamil words, to the clang of the typewriter. Sentences would jump out of him, the typewriter would struggle to keep up, and words would start again. When permitted inside the room, I always found it boring in a few minutes.

He was strict and unapproachable, more in my imagination than in reality. Most of my holidays I spent in his house, but I tried hard to avoid him. There would always be some small sin I had committed that he was bound to pull me up for. His idea of playtime was colouring books, mine included violent games, the victim usually being my brother.

I detested Tamil and never read anything outside of school work. His first short story that I read was a little known translation into English of Stamp Album. When I told him about it, he was surprised and asked for the book. He didn’t realise that the story had been translated. That incident left no impression on my mind. I thought compared to Sherlock Holmes, Stamp Album was nothing.

Then for years, he was absent from my life. I rarely visited my grandparents and for a time it seemed like I didn’t know them anymore. My father would keep mentioning JJ: Sila Kurippugal in his conversations about books. After one such conversation, I dusted a heavily marked first edition copy of the book from the loft and looked at it. I had never read a Tamil novel before and I seriously doubted I would read this one. The first sentence on JJ's death was striking. I was curious about how a writer could start a novel with his main character dying right in the first line. I kept reading and over three or four days finished the book.

I realised then that books do change your life. And for the first time in years, I wanted to meet my grandfather. I went over to his place and told him that I had read JJ. He wanted to talk but I grew shy. He said he would like to suggest a couple of books that I might like, but I somehow slipped away.

Years later, after my mother died and father became ill, I moved to my grandparents’ home. I read a lot of him during this time which gave me the confidence to ask him questions about his work, his idea of creativity and virtually everything under the sun. I joined him in his evening walks and we would have long conversations. Looking back, I realise that I was more naive that I thought I was and he was more patient than he needed to be.

He had a mind that always thought things through. He could with great style incisively analyse issues, a quality that make his essays valuable. But there are aspects to him like his conversations — funny, clever and poignant — that went unrecorded. He also laughed like no one else, his facial muscles completely loose, his mouth wide, his eyebrows as if frowning.

I remember talking to him when he had just begun his third novel — Kuzhanthaigal Pengal Angal. From random conversations to the manuscript to the published book, the creative process was fascinating. He approached it like a 10 to 5 job. Even 10 minutes away from his work affected him badly.

It was as if he had tons to say even after 50 years at it. He would always keep grumbling about distractions that keep him away from work. He had a spirit that wasn’t easily suppressed. From the way he exercised in the morning till in the night when he read himself to sleep, he displayed an enthusiasm for life that I envied.

One of the first things that my uncle Kannan did around the time he revived Kalachuvadu, the literary magazine, in the mid 90s, was to publish my grandfather's collection of poems. Unlike his other works, the poems kept growing on me with every reading. When dramatised or sung, these poems reveal a dimension to them that make me marvel at their writer.

He was in great health when he wrote the short stories collected in Maria Thamuvukku Ezhuthiya Kaditham in 2003. It’s hard to believe that barely two years later, he is no more.

When news that he had been admitted to hospital came, I grew restless. His voice when he had last spoken to me had been really subdued. Even after seeing his body in the casket at the funeral, the reality of his death never hit home. It was unreal to see people crying unabashedly and to walk among showering petals to the cemetery alongside his body.

My relationship with him was in many ways unfulfilled. I had somehow deluded myself to thinking that he would always be there. Today, I regret deeply that another conversation with him is impossible.

The day after his funeral, my six-year-old cousin imitated my grandfather's ritualistic arrival at the dining table for lunch. The door of his room would open, my grandfather would emerge humming a tune and walk the few feet to the large hall, switch on the fan and sit in his regular chair. None of us look at the time. It would always be 1 pm.

Most people, I think, go through life without ever having a shot at what they really want to do. My grandfather decided in his teens that he wanted to be a writer and pursued that path with rigour. Amidst all this sorrow, that’s one thing that makes me happy. Happy of his fulfilled life and our unfulfilled relationship.